Saturday, 6 December 2025

Friday, 24 October 2025

Between River and Sea by Dervla Murphy

Her goal was to understand everyday life and political realities so she spent time in villages, refugee camps, and ordinary homes, listening to the personal stories of her Israeli and Palestinian hosts and recording everything in her journal. The result is a book which pulls you along with her narrative skill then stops you in your tracks as she gives yet another another example of man's inhumanity to man. It is both immensely readable and profoundly disturbing.

Despite the fraught relationships, restrictions and many frustrations Murphy insists on seeing both Israelis and Palestinians as human beings. She condemns dehumanisation on both sides and tries to find areas of mutual understanding.

Much of the book focuses on life under Israeli occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. She documents restrictions on movement, checkpoints, settlement expansion, and home demolitions. Murphy sees these as daily expressions of systemic injustice that crush Palestinian dignity.

On the other side she also meets Israeli peace activists, ex-soldiers, and settlers and finds some Israelis deeply conflicted — aware of the moral toll of occupation but trapped by security fears and political conformity.

She also argues that Western governments, particularly the UK, EU, and US, have enabled the continuation of the conflict by failing to hold Israel to account for its breeches of international agreements. But she also condemns the suicide campaign of the 2nd Intifada that produced a powerful Israeli reaction and has had a huge impact on Palestinian society.

She meets people who despite the strong antagonism and even hatred on both sides who are trying to live normal lives and courageous members of both communities who seek to cross the divides and work for peace.

Murphy is clearly very sympathetic to the Palestinian experience and sharply critical of Israeli state policy, but she distinguishes between Israeli government actions and individual Israelis. Her resolution of the conflict at the time of writing was for a single democratic state involving all sides – now clearly out of the question.

Between River and Sea gives a grass roots perspective on perhaps the most intractable of all conflicts. Dervla Murphy is a great storyteller. The reader is carried along by her observations of people and places, the setting of context from history, ancient and modern, her persistence in going places and meeting people, her beer drinking and her ability to cut through the complexities of religion and politics to reveal the real lives of real people.

Saturday, 18 October 2025

Stephen Fry: The Lure of Language

Peroration

Horticulturally, we are encouraged to rewild our gardens and fields, dig up the lawns, sow wildflowers, to let our hedges go without haircuts and to encourage the bursting forth of colour and growth. So let's set our word gardens free too.

Did I really say, 'word gardens'? I'm so sorry.

But truly, let's reclaim the fun and frolic of language.

Let's release it from the lantern-jawed severity and affectless restraint, from

austere solemnity.

Here's to an individual way with language: embarrassing,

overdone, over seasoned, over spiced, borrowed, cannibalised, veneered,

finessed, faked and finagled as it may be.

Let there be freedom in your utterance and let there be

delight. Let there be textural pleasure. Let there be silken words and flinty

words and sodden speeches and soaking speeches, crackling utterance and

utterance that quivers and wobbles like rennet.

Let there be rapid firecracker phrases and words that ooze

like a lake of lava. Don't rein it in. Don't fear it. Don't believe it belongs

to anybody else.

Don't let anyone bully you into believing that there are

rules and secrets of grammar and verbal deployment to which you are not privy. Just

let the words fly from your lips and your pen. Make up silly nicknames for

those you love and those you despise. Devise nonsense words and mad melodious

mantras. Don't sing in the shower, try out accents, argots, nonsense, Tommy-rotten

gibberish.

Give your words rhythm and depth and height and silliness. Give

them filth and form and majestic stupidity. Mix the slangy with the grand, the

noble with the naughty.

Swear sweetly and curse caressingly. Truth is constructed,

aesthetes, teachers, through artifice.

We can believe in the truth of masks - reality cannot be

trusted, appearances can. Reality is shifting, obscure and unreliable. Building

palaces of gorgeous, coloured words is an act of belief, a gift that proclaims

us all worthy of palaces.

Towers of grey breeze-block words, insult our capacity for

language and deny us the thrones in the realm of language that are our

birthright.

Demagogues use words to blame, enrage, divide and inflame. Can

we not venture to use them to enchant, connect, solace and inspire?

Words are free and all words, light and frothy, dour and

dappled, firm and sculpted as they may be, bear the history of their passage

from lip to lip over thousands of years. Words are weaponry and witchcraft.

They are pedigrees and passports, crowns and costume, and

they are ours.

Succumb to their lure. Buff their current dullness to a

dazzling new shine, sheen and gleam.

Play gracefully, disport yourselves disgracefully and make Oscar

proud.

Thank you.

Full lecture here:

Monday, 23 June 2025

The Ground Beneath Her Feet by Salman Rushdie

Even when the novel begins to focus on the three-legged journey of Ormus, Vina and Rai, Rushdie veers off the main track, as though, not content with building a house he needs lots of out-buildings too. He says about his novel, Midnight’s Children, “I was thinking of India’s oral narrative traditions which were a form of storytelling in which digression was almost the basic principle; the storyteller could tell, in a sort of whirling cycle, a fictional tale, a mythological tale, a political story and an autobiographical story”

Rushdie’s mind is stuffed full of knowledge; a cornucopia of literature, philosophy, history, mythology, religion, and music which he pours out onto the page. There are passing references to:

Homer, Aristotle, Plato, Hamlet, Huxley (Brave New World), Voltaire (Candide), Amazing Grace, Alice in Wonderland, Dickens (Bleak House) Orwell (1984), The Beatles (Yesterday) Guys & Dolls, Lucky Jim, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Zen & The Art of Motor Cyle Maintenance, The Jungle Book, Ps 30 v5 is turned on its head (Weeping tarries for the night but joy comes in the morning) T S Eliot (p145. The Hollow Men, “Between the conception and the creation, Between the emotion and the response, fall the shadow”) Even Donald Trump gets an oblique look-in (p17: Zen and The Art of The Deal).

He says:

- “The idea was to take one of the great archetypal myths and to retell it in a way that makes sense now, in our time, in the world of rock music and fame.”

- “Pop culture creates its own gods and monsters, and I wanted to explore how those forces shape people's lives and their emotional realities.”

- “The book is about borderlessness—not just geographical but emotional and aesthetic too.”

- “I was interested in parallel realities—not science fiction, but the idea that what we think of as the real world is full of inconsistencies, distortions, and inventions.”

He has acknowledged the novel contains deeply personal elements, particularly in how it portrays loss and mourning. The title itself—The Ground Beneath Her Feet—evokes the sense of disorientation and collapse that comes from losing someone you love.

He also says:

“I have always been attracted to capacious, largehearted fictions, books that try to gather up large armfuls of the world”, books of the type that Henry James had called “loose, baggy monsters”,

Well, this was certainly a loose baggy monster. Too loose and too baggy for me. As I’ve said before, I am torn between being a rationalist and a romantic, so I enjoyed the tug-of-war between these ways of looking at human existence. Rai the rational observer of the irrational Ormus, with Vina oscillating between them both.

There are parallels with the German romantic Novalis. Ormus falls for 12 year-old Vina and “sees” another world; Novalis fell for 12 year-old Sophie von Khun and wrote: "One day, I felt the certainty of immortality, like the touch of a hand……As things are, we are the enemies of the world and foreigners to this earth."

Rushdie’s ability as a writer and story-teller are clear to see but the central plot line, the supposedly perfect and all-consuming love between Vina and Ormus was simply not believable. His attempt to recreate the Orpheus/Eurydice myth fell apart at this point.

I annotated my copy of the book vigorously. It helped to engage with the writing and also give vent to my frustrations and disagreements. Some comments I made were:

- Pretentious p279

- New age nonsense p326

- Love? Really! p383

- Just don't believe this idea - nonsense. P386

- Profound truth or gobbledegook? P389

- Skip - why include this? P390/391

- Perfection of love or more nonsense? P 424

- Over the top. P480

- Complete nonsense Rushdie! p482/483

- Too much navel gazing myth, philosophy - is this a novel or what? P502

- This book is dribbling into nothingness. P558

However, having struggled and fought my way through the book like a wanderer in a desert plodding towards the mirage of Vina and Ormus, the shifting sand beneath my feet, I found enough oases of enjoyment to keep on going.

Wednesday, 30 April 2025

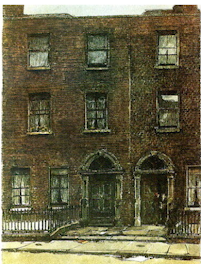

Ulysses by James Joyce - an intro

The very idea of annotating Ulysses overwhelm. Both of the questions, "Where does one begin? and, perhaps more practically, "Where does one stop?" utterly disconcert.

I've put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that's the only way of insuring one's immortality.

- Cicones: A raid gone awry.

- Lotus-Eaters: Men who consume the forgetful lotus plant.

- Cyclops Polyphemus: Odysseus blinds the one-eyed giant, inciting Poseidon's wrath.

- Aeolus: The wind god gifts a bag of winds; the crew's curiosity leads to misfortune.

- Laestrygonians: Cannibalistic giants destroy all ships but Odysseus's.

- Circe: The enchantress turns men into swine; Odysseus, protected by Hermes, resists and stays for a year.

- Underworld: Odysseus consults the prophet Tiresias and encounters spirits of the dead.

- Sirens: Their song lures sailors to doom; Odysseus listens while bound to the mast.

- Scylla and Charybdis: Navigating between a six-headed monster and a deadly whirlpool.

- Thrinacia: Crew slaughters sacred cattle of Helios; Zeus punishes them with a storm, leaving Odysseus adrift

The Three Main Characters

Odysseus the warrior is transposed to Leopold Bloom, a middle-aged jewish advertising salesman: Both are wandering figures, facing obstacles on their journey home.

Telemachus, Odysseus' son, is mirrored by Stephen Dedalus a scholar and teacher. Both struggle with identity and father figures.

Penelope, Odysseus’ wife, becomes Molly Bloom. But where Penelope waits faithfully for the return of her husband, Molly has an affair.

What follows is a taster of both the novel and the guide. I have copied the first lines of text of each of the 18 sections from Project Gutenburg, followed by the first part of the guide notes from Hastings' website, so you can see how the novel changes in character and style and how the guide helps. Occassionally I have removed parts of the text, shown by ..............

Ch1. Telemachus

Stephen Dedalus is searching for a father figure and meaning.

Introibo ad altare Dei*. Halted, he peered down the dark winding stairs and called out coarsely:

Come up, Kinch! Come up, you fearful jesuit!

Solemnly he came forward and mounted the round gunrest. He faced about and blessed gravely thrice the tower, the surrounding land and the awaking mountains. Then, catching sight of Stephen Dedalus, he bent towards him and made rapid crosses in the air, gurgling in his throat and shaking his head. Stephen Dedalus, displeased and sleepy, leaned his arms on the top of the staircase and looked coldly at the shaking gurgling face that blessed him, equine in its length, and at the light untonsured hair, grained and hued like pale oak.

*I will go to the altar of God

Guide

Ulysses opens on the rooftop of the Martello Tower at 8:00 am on the morning of June 16th, 1904. Buck Mulligan, a medical student in his 20s, looks out over Sandycove, a bayside suburb just south of Dublin, and begins to parody the Catholic mass as he prepares to shave his face. He calls back down “the dark winding stairs” for Stephen Dedalus to join him in the mild morning air.

My general advice: seek explanations for the allusions that genuinely pique your curiosity, but please don’t feel compelled to look up everything that you don’t know. Lots of stuff is going to fly over your head. Let it.

Ch2. Nestor

Stephen is teaching in a school. He talks with Mr. Deasy, mirroring Telemachus’s search for advice.—Tarentum, sir.

—Very good. Well?

—There was a battle, sir.

—Very good. Where?

The boy’s blank face asked the blank window.

Fabled by the daughters of memory. And yet it was in some way if not as memory fabled it. A phrase, then, of impatience, thud of Blake’s wings of excess. I hear the ruin of all space, shattered glass and toppling masonry, and time one livid final flame. What’s left us then?

—I forget the place, sir. 279 B. C.

—Asculum, Stephen said, glancing at the name and date in the gorescarred book.

—Yes, sir. And he said: Another victory like that and we are done for.

That phrase the world had remembered*. A dull ease of the mind. From a hill above a corpsestrewn plain a general speaking to his officers, leaned upon his spear. Any general to any officers. They lend ear.

—You, Armstrong, Stephen said. What was the end of Pyrrhus?

—End of Pyrrhus, sir?

—I know, sir. Ask me, sir, Comyn said.

—Wait. You, Armstrong. Do you know anything about Pyrrhus?

* Pyrric victory

Guide quote

The “Nestor” episode depicts Stephen at work as a teacher at a private boys’ school in Dalkey, which is about a 20 minute walk south from the Martello Tower. We know Stephen departed the tower no sooner than 8:45 am (the bells chimed three quarters past the hour at the end of “Telemachus”), so he presumably arrives a few minutes past 9:00 am. He is late to work.

Ch3 Proteus

Stephen wanders Sandymount Strand, contemplating perception and reality (shifting like Proteus, a sea god who could assume many forms).(My note: this is the point where many give up. Everything is going on inside Stephen's head - stream of consciousness writing. I just ploughed on, taking Hastings advice to let words, sentences and meaning fly over my head, and then began to actually find some meaning and even enjoyment)

Ineluctable modality of the visible: at least that if no more, thought through my eyes. Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide, that rusty boot. Snotgreen, bluesilver, rust: coloured signs. Limits of the diaphane. But he adds: in bodies. Then he was aware of them bodies before of them coloured. How? By knocking his sconce against them, sure. Go easy. Bald he was and a millionaire, maestro di color che sanno. Limit of the diaphane in. Why in? Diaphane, adiaphane. If you can put your five fingers through it it is a gate, if not a door. Shut your eyes and see.

Guide

The “Proteus” episode depicts the erudite musings of Stephen Dedalus as he walks along Sandymount Strand just before 11:00 am. Dense and difficult to follow, “Proteus” is where most first time readers of Ulysses throw in the towel. Don’t. Despite the fact that even the most serious Joycean could spend an entire career reading deeply in this episode, you needn’t get bogged down if you don’t want to. In this guide, I’ll give you what you need to continue your momentum toward meeting Mr. Bloom in the next episode.

Ch4 Calypso

Leopold Bloom is introduced at home with Molly; domestic details replace the mythic.Kidneys were in his mind as he moved about the kitchen softly, righting her breakfast things on the humpy tray. Gelid light and air were in the kitchen but out of doors gentle summer morning everywhere. Made him feel a bit peckish.

The coals were reddening.

Another slice of bread and butter: three, four: right. She didn’t like her plate full. Right. He turned from the tray, lifted the kettle off the hob and set it sideways on the fire. It sat there, dull and squat, its spout stuck out. Cup of tea soon. Good. Mouth dry. The cat walked stiffly round a leg of the table with tail on high.

—Mkgnao!

—O, there you are, Mr Bloom said, turning from the fire.

The cat mewed in answer and stalked again stiffly round a leg of the table, mewing. Just how she stalks over my writingtable. Prr. Scratch my head. Prr.

Mr Bloom watched curiously, kindly the lithe black form. Clean to see: the gloss of her sleek hide, the white button under the butt of her tail, the green flashing eyes. He bent down to her, his hands on his knees.

Guide

Just as Book Five of The Odyssey shifts focus from Telemachus to Odysseus, the “Calypso” episode restarts the story of Ulysses in Mr. Bloom’s home (7 Eccles Street) at 8:00 am on the morning of June 16th 1904. Leaving behind Stephen’s intensity and density of thought, you’ll likely find Mr. Bloom’s arrival on the page a relief. As we begin the novel’s second triad of episodes in the initial style, the text continues to provide intimate access to the focalized character’s thoughts by the techniques of inner monologue and free indirect discourse, but the third person narrator now adopts Mr. Bloom’s comic sensibility and groundedness in the physical world. We swap the erudition of Stephen’s interiority for Mr. Bloom’s reliance on external stimuli for his frames of reference and mental activity.

Ch5 Lotus Eaters

Bloom drifts through Dublin, distracted, passive, like the dreaminess of the Lotus-Eaters.Guide

The opening of “Lotus-Eaters” finds Bloom on the south bank of the Liffey, and he will cover about a mile over the course of this episode. Note that Mr. Bloom’s southerly walk echoes Stephen’s concurrent commute from the Tower to the school, and, for future reference, note also that he probably takes the same route (though in the opposite direction) as he will take home from the Cabman’s shelter about 15 hours hence.

Ch6 Hades

Bloom attends Paddy Dignam’s funeral — confronting mortality (a "descent" into the underworld).—Come on, Simon.

—After you, Mr Bloom said.

Mr Dedalus covered himself quickly and got in, saying:

—Yes, yes.

—Are we all here now? Martin Cunningham asked. Come along, Bloom.

Mr Bloom entered and sat in the vacant place. He pulled the door to after him and slammed it twice till it shut tight. He passed an arm through the armstrap and looked seriously from the open carriagewindow at the lowered blinds of the avenue. One dragged aside: an old woman peeping. Nose whiteflattened against the pane. Thanking her stars she was passed over. Extraordinary the interest they take in a corpse. Glad to see us go we give them such trouble coming. Job seems to suit them. Huggermugger in corners. Slop about in slipperslappers for fear he’d wake. Then getting it ready. Laying it out. Molly and Mrs Fleming making the bed. Pull it more to your side. Our windingsheet. Never know who will touch you dead. Wash and shampoo. I believe they clip the nails and the hair. Keep a bit in an envelope. Grows all the same after. Unclean job.

All waited. Nothing was said. Stowing in the wreaths probably. I am sitting on something hard. Ah, that soap: in my hip pocket. Better shift it out of that. Wait for an opportunity.

All waited. Then wheels were heard from in front, turning: then nearer: then horses’ hoofs. A jolt. Their carriage began to move, creaking and swaying. Other hoofs and creaking wheels started behind. The blinds of the avenue passed and number nine with its craped knocker, door ajar. At walking pace.

They waited still, their knees jogging, till they had turned and were passing along the tramtracks. Tritonville road. Quicker. The wheels rattled rolling over the cobbled causeway and the crazy glasses shook rattling in the doorframes.

—What way is he taking us? Mr Power asked through both windows.

—Irishtown, Martin Cunningham said. Ringsend. Brunswick street.

Mr Dedalus nodded, looking out.

Guide

As Mr. Bloom has planned all morning, he joins Paddy Dignam’s funeral cortege at 11 am. Together with Martin Cunningham, Jack Power, and Simon Dedalus (Stephen’s father), Mr. Bloom will traverse Dublin by horse-drawn carriage, beginning at the Dignam home in the southeast corner of central Dublin (just east of the Aviva Stadium noted on the Google Earth path to the right), going through the heart of the City Center, and ending at Glasnevin Cemetery in the north).

In Homer’s Odyssey, “Hades” is the land of the dead, to which Odysseus travels in order to learn from the great prophet Tiresias how he might return to his home in Ithaca. Likewise, Mr. Bloom in this episode visits the memories of loved one who have passed away and wrestles with thoughts of his own home, where his wife Molly and her lover Blazes Boylan will meet later this afternoon.

Ch7 Aeolus

At a newspaper office; the "winds" are metaphors for gossip, chatter, and headlines.—Rathgar and Terenure!

—Come on, Sandymount Green!

Right and left parallel clanging ringing a doubledecker and a singledeck moved from their railheads, swerved to the down line, glided parallel.

—Start, Palmerston Park!

—There it is, Red Murray said. Alexander Keyes.

—Just cut it out, will you? Mr Bloom said, and I’ll take it round to the Telegraph office.

The door of Ruttledge’s office creaked again. Davy Stephens, minute in a large capecoat, a small felt hat crowning his ringlets, passed out with a roll of papers under his cape, a king’s courier.

Red Murray’s long shears sliced out the advertisement from the newspaper in four clean strokes. Scissors and paste.

—I’ll go through the printingworks, Mr Bloom said, taking the cut square.

—Of course, if he wants a par, Red Murray said earnestly, a pen behind his ear, we can do him one.

—Right, Mr Bloom said with a nod. I’ll rub that in.

Guide

The “Aeolus” episode, with its newspaper headlines, represents the first of many chapters where Joyce pushes the boundaries of the novel as a form. Can a novel contain newspaper headlines? Is a novel still a novel if ⅕ th of it is written as a play? What if it also contains a catechism? How do these devices alter the reading experience?

Joyce saw all forms of language - from Dublin slang to Deuteronomy, from pop music lyrics to Virgil’s Eclogues, from advertising slogans to Shakespeare - as fodder for the great project of Ulysses. In the case of this episode’s headlines (which Joyce added to the text at proof stage) we immediately notice their effect of simultaneously interrupting and framing the prose and narration.

In the schema, Joyce identified the lungs as the organ for this chapter; indeed, the episode features lots of comings and goings (inhales and exhales), and the diction is suffused with references to air and wind. In terms of the correspondence to Homer, the episode is named for Aeolus, the keeper of the winds, who gives Odysseus a magical sack of winds; appropriately, this chapter is filled with the hot air of political speeches, rhetorical devices, and the inflated prose of newspapers and newspapermen.

Ch8 Lestrygonian

Bloom moves through Dublin at lunchtime; the giant Lestrygonians become gluttonous citizens.Pineapple rock, lemon platt, butter scotch. A sugarsticky girl shovelling scoopfuls of creams for a christian brother. Some school treat. Bad for their tummies. Lozenge and comfit manufacturer to His Majesty the King. God. Save. Our. Sitting on his throne sucking red jujubes white.

A sombre Y. M. C. A. young man, watchful among the warm sweet fumes of Graham Lemon’s, placed a throwaway in a hand of Mr Bloom.

Heart to heart talks.

Bloo... Me? No.

Blood of the Lamb.

His slow feet walked him riverward, reading. Are you saved? All are washed in the blood of the lamb. God wants blood victim. Birth, hymen, martyr, war, foundation of a building, sacrifice, kidney burntoffering, druids’ altars. Elijah is coming. Dr John Alexander Dowie restorer of the church in Zion is coming.

Is coming! Is coming!! Is coming!!!

All heartily welcome.

Paying game. Torry and Alexander last year. Polygamy. His wife will put the stopper on that. Where was that ad some Birmingham firm the luminous crucifix. Our Saviour. Wake up in the dead of night and see him on the wall, hanging. Pepper’s ghost idea. Iron Nails Ran In.

..................

From Butler’s monument house corner he glanced along Bachelor’s walk. Dedalus’ daughter there still outside Dillon’s auctionrooms. Must be selling off some old furniture. Knew her eyes at once from the father. Lobbing about waiting for him. Home always breaks up when the mother goes. Fifteen children he had. Birth every year almost. That’s in their theology or the priest won’t give the poor woman the confession, the absolution. Increase and multiply. Did you ever hear such an idea? Eat you out of house and home. No families themselves to feed. Living on the fat of the land. Their butteries and larders.

Guide

With Stephen heading off at the end of “Aeolus” for a few pints, Mr. Bloom is once again the sole focalized character of the “Lestrygonians” episode. We join him at 1:00 pm - lunchtime - as he moves south on O’Connell Street from the newspaper office toward the River Liffey. Food is on the brain as he passes Graham Lemon’s Confectioner’s Hall, a candy shop. The episode is peppered with many references to food, and the schema lists “peristaltic prose” as the technique of this episode. In digestion, peristalsis refers to the intestinal muscles contracting and relaxing to push food along; Joyce’s style in “Lestrygonians” employs this concept as Bloom moves in starts and stops through the belly of downtown Dublin.

He accepts an evangelical flyer from a young YMCA fellow, skims its contents (“Are you saved? … Elijah is coming” (8.10-13)), before dismissing this sort of proselytizing advertisement as a for-profit enterprise. As he approaches the River Liffey, he glances to his right to see Dilly Dedalus waiting outside of Dillon’s auction house on Bachelor’s Walk. Stephen’s little sister appears malnourished and wears a tattered dress. Bloom presumes that she is selling off furniture and reflects on the collapse of the Dedalus household since the passing of Stephen’s mother; he notes the folly of enormous Catholic families.

Ch9 Scylla and Charybdis

Stephen debates in the library, intellectual dangers replacing physical monsters.Urbane, to comfort them, the quaker librarian purred:

—And we have, have we not, those priceless pages of Wilhelm Meister. A great poet on a great brother poet. A hesitating soul taking arms against a sea of troubles, torn by conflicting doubts, as one sees in real life.

He came a step a sinkapace forward on neatsleather creaking and a step backward a sinkapace on the solemn floor.

A noiseless attendant setting open the door but slightly made him a noiseless beck.

—Directly, said he, creaking to go, albeit lingering. The beautiful ineffectual dreamer who comes to grief against hard facts. One always feels that Goethe’s judgments are so true. True in the larger analysis.

Twicreakingly analysis he corantoed off. Bald, most zealous by the door he gave his large ear all to the attendant’s words: heard them: and was gone.

Two left.

—Monsieur de la Palice, Stephen sneered, was alive fifteen minutes before his death.

—Have you found those six brave medicals, John Eglinton asked with elder’s gall, to write Paradise Lost at your dictation? The Sorrows of Satan he calls it.

Smile. Smile Cranly’s smile.

First he tickled her

Then he patted her

Then he passed the female catheter

For he was a medical

Jolly old medi...

—I feel you would need one more for Hamlet. Seven is dear to the mystic mind. The shining seven W.B. calls them.

Glittereyed his rufous skull close to his greencapped desklamp sought the face bearded amid darkgreener shadow, an ollav, holyeyed. He laughed low: a sizar’s laugh of Trinity: unanswered.

Orchestral Satan, weeping many a rood

Tears such as angels weep.

Ed egli avea del cul fatto trombetta.

Guide

The ninth episode of the novel, “Scylla & Charybdis,” takes place in the National Library, where Stephen Dedalus will deliver his much-anticipated (though sparsely attended) lecture on Shakespeare and Hamlet. Excepting the second half of “Aeolus,” we have largely been in Bloom’s mind since “Proteus,” so the return to the intellectual density, social tension, and discursive loftiness of Stephen’s thoughts in “Scylla & Charybdis” can be somewhat jarring…perhaps even off-putting. Some readers may be tempted to quit. Don’t!

Like with “Proteus,” my goal is to get you through this episode and on to the rest of the book; indeed, a comprehensive guide to this episode would necessitate literally thousands of explanations and revelations. Just about every line contains a Shakespearean allusion!

(My note: in the notes on this section at the back of the Oxford World's Classic edition one page required nearly two pages of notes)

Ch10 Wandering Rocks

A fragmented view of Dublin's citizens; interweaving paths, like "rocks" blocking progress.The superior, the very reverend John Conmee S. J. reset his smooth watch in his interior pocket as he came down the presbytery steps. Five to three. Just nice time to walk to Artane. What was that boy’s name again? Dignam. Yes. Vere dignum et iustum est. Brother Swan was the person to see. Mr Cunningham’s letter. Yes. Oblige him, if possible. Good practical catholic: useful at mission time.

A onelegged sailor, swinging himself onward by lazy jerks of his crutches, growled some notes. He jerked short before the convent of the sisters of charity and held out a peaked cap for alms towards the very reverend John Conmee S. J. Father Conmee blessed him in the sun for his purse held, he knew, one silver crown.

Father Conmee crossed to Mountjoy square. He thought, but not for long, of soldiers and sailors, whose legs had been shot off by cannonballs, ending their days in some pauper ward, and of cardinal Wolsey’s words: If I had served my God as I have served my king He would not have abandoned me in my old days. He walked by the treeshade of sunnywinking leaves: and towards him came the wife of Mr David Sheehy M.P.

—Very well, indeed, father. And you, father?

Father Conmee was wonderfully well indeed. He would go to Buxton probably for the waters. And her boys, were they getting on well at Belvedere? Was that so? Father Conmee was very glad indeed to hear that. And Mr Sheehy himself? Still in London. The house was still sitting, to be sure it was. Beautiful weather it was, delightful indeed. Yes, it was very probable that Father Bernard Vaughan would come again to preach. O, yes: a very great success. A wonderful man really.

Guide

As the anxiety of navigating “Scylla and Charybdis” dissipates, Joyce offers “Wandering Rocks” as an interlude to mark the midway point in the novel (if not by pages, at least by episodes). Written as 18 mini-episodes (plus a concluding coda) that occur across the city of Dublin between 2:55 and 4:00 pm, “Wandering Rocks” is often referred to as Ulysses in miniature. Indeed, the episode’s interlocking parts and painstaking attention to time and place inspires much the same awe and appreciation the reader feels for the novel as a whole.

The schema lists “mechanics” as the art for this episode, and we can think of each of the 18 sections as a gear in the Dublin machine. Short scenes or occurrences in one section might reappear (or pre-appear) in other sections of the episode divorced from space (but not time) in a device called interpolation. Think of these interpolations as teeth from one gear momentarily interlocking with another gear in the turning Dublin machine.

Ch11 Sirens

In the bar/music hall, Bloom is tempted by the "siren song" of sensuality.(My note: this makes a bit more sense when you read the Guide and discover that Bronze & Gold are two young women (different hair colour) staring out of a window watching a procession go by)

Bronze by gold heard the hoofirons, steelyringing.

Imperthnthn thnthnthn.

Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips.

Horrid! And gold flushed more.

A husky fifenote blew.

Blew. Blue bloom is on the.

Goldpinnacled hair.

A jumping rose on satiny breast of satin, rose of Castile.

Trilling, trilling: Idolores.

Peep! Who’s in the... peepofgold?

Tink cried to bronze in pity.

And a call, pure, long and throbbing. Longindying call.

Decoy. Soft word. But look: the bright stars fade. Notes chirruping answer.

O rose! Castile. The morn is breaking.

Jingle jingle jaunted jingling.

Coin rang. Clock clacked.

Avowal. Sonnez. I could. Rebound of garter. Not leave thee. Smack. La cloche! Thigh smack. Avowal. Warm. Sweetheart, goodbye!

Jingle. Bloo.

Boomed crashing chords. When love absorbs. War! War! The tympanum.

A sail! A veil awave upon the waves.

Lost. Throstle fluted. All is lost now.

Horn. Hawhorn.

When first he saw. Alas!

Full tup. Full throb.

Warbling. Ah, lure! Alluring.

Martha! Come!

Clapclap. Clipclap. Clappyclap.

Goodgod henev erheard inall.

Deaf bald Pat brought pad knife took up.

A moonlit nightcall: far, far.

I feel so sad. P. S. So lonely blooming.

Listen!

The spiked and winding cold seahorn. Have you the? Each, and for other, plash and silent roar.

Pearls: when she. Liszt’s rhapsodies. Hissss.

You don’t?

Did not: no, no: believe: Lidlyd. With a cock with a carra.

Black. Deepsounding. Do, Ben, do.

Guide

Whereas most of the episodes in Ulysses begin in medias res (in the middle of things) and at a remove (temporally, spatially, or both) from the previous episode’s conclusion, characters in Episode 11 pick up almost exactly where they left off in Episode 10. You’ll recall that the coda of the “Wandering Rocks” episode depicts the procession of the Viceregal cavalcade through the heart of the city and shows various Dubliners as they watch and react to the grandeur of this event. The “Sirens” episode opens its action by repeating nearly verbatim the description of two barmaids, Miss Douce (bronze) and Miss Kennedy (gold), peering through the windows of the Ormond Hotel bar to catch a glimpse as the procession rolls along the north bank of the Liffey at 3:38 pm.

The correspondence of the sirens refers to two birdwomen whose beautiful singing tempts sailors off course, luring their ships to wreck on a craggy island. In The Odyssey, Odysseus plugs his crew’s ears with wax to prevent them from hearing the sirens’ song; Odysseus himself, clever enough to have his cake and eat it too, ties himself to his mast so that he can enjoy the sirens’ song while preventing himself from steering the ship toward the temptresses. Jackson I. Cope argues that Miss Douce and Miss Kennedy are the sirens, trying to tempt Boylan from his imminent adultery with Molly. Additionally, he suggests that Bloom’s “impulse to interfere in their affair is a siren-song that would destroy them all.”

With this episode’s depiction of singing performances along with its musical prose elements (such as onomatopoeia, linguistic refrains, and syncopated syntax), “Sirens” directly engages and seeks to replicate the qualities of music, which is the art listed on the Gilbert/Linati Schemas for this episode. The prominence of this musical style in the episode’s discourse signals a departure from what we have come to regard as the normal narration of the novel; in “Sirens,” the Arranger’s influence is dominant.

The first 62 lines of the episode are jarring and largely incomprehensible to the first-time reader. In The Argument of Ulysses, Stanley Sultan describes this opening section as an “overture,” introducing the major notes of the chapter’s language and plot. While Sultan’s label is apt, I also like to think of this section as an orchestra warming up prior to a performance; the reader is like an audience listening to musicians practicing trills and phrases of the composition to be performed. It is cacophony here, but it will all make sense when properly arranged and elaborated upon in the performance/chapter ahead.

Ch12 Cyclops

Bloom is attacked verbally by a nationalist ("The Citizen"), echoing the Cyclops's one-eyed view.I was just passing the time of day with old Troy of the D. M. P. at the corner of Arbour hill there and be damned but a bloody sweep came along and he near drove his gear into my eye. I turned around to let him have the weight of my tongue when who should I see dodging along Stony Batter only Joe Hynes.

—Lo, Joe, says I. How are you blowing? Did you see that bloody chimneysweep near shove my eye out with his brush?

—Soot’s luck, says Joe. Who’s the old ballocks you were talking to?

—Old Troy, says I, was in the force. I’m on two minds not to give that fellow in charge for obstructing the thoroughfare with his brooms and ladders.

—What are you doing round those parts? says Joe.

—Devil a much, says I. There’s a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the garrison church at the corner of Chicken lane—old Troy was just giving me a wrinkle about him—lifted any God’s quantity of tea and sugar to pay three bob a week said he had a farm in the county Down off a hop-of-my-thumb by the name of Moses Herzog over there near Heytesbury street.

—Circumcised? says Joe.

—Ay, says I. A bit off the top. An old plumber named Geraghty. I’m hanging on to his taw now for the past fortnight and I can’t get a penny out of him.

—That the lay you’re on now? says Joe.

—Ay, says I. How are the mighty fallen! Collector of bad and doubtful debts. But that’s the most notorious bloody robber you’d meet in a day’s walk and the face on him all pockmarks would hold a shower of rain. Tell him, says he, I dare him, says he, and I doubledare him to send you round here again or if he does, says he, I’ll have him summonsed up before the court, so I will, for trading without a licence. And he after stuffing himself till he’s fit to burst. Jesus, I had to laugh at the little jewy getting his shirt out. He drink me my teas. He eat me my sugars. Because he no pay me my moneys?

Guide

The “Cyclops” episode of Ulysses tells the story of what occurred in Barney Kiernan’s pub between the hours of 5:00 and 6:00 pm from the narrative perspective of a working class Dubliner. I want to emphasize the past tense of “occurred” in the previous sentence because the nameless narrator (referred to as the Nameless One or “I”) is probably telling this story in a pub at some later point - since he lacks financial means, storytelling is the currency he exchanges for drinks. Perhaps the closest the novel approaches to moralizing, the “Cyclops” episode directly engages questions of nationalism and prejudice, love and hate, violence and injustice, but Joyce only provides the opportunity to engage these lofty topics while viewing Bloom through the eyes of someone prejudiced against him.

If not the climax of the novel, the “Cyclops” episode certainly represents a significant flashpoint in the events of Bloomsday. The anti-Semitism that has lingered in the background of many of Bloom’s social interactions throughout the day emerges as an overt and aggressive force, principally represented in the character of the Citizen, an Irish nationalist with an eyepatch and a myopic view of who qualifies as truly Irish.

Ch13 Nausicaa

Bloom encounters Gerty MacDowell on the beach, a parody of romantic ideals.The summer evening had begun to fold the world in its mysterious embrace. Far away in the west the sun was setting and the last glow of all too fleeting day lingered lovingly on sea and strand, on the proud promontory of dear old Howth guarding as ever the waters of the bay, on the weedgrown rocks along Sandymount shore and, last but not least, on the quiet church whence there streamed forth at times upon the stillness the voice of prayer to her who is in her pure radiance a beacon ever to the stormtossed heart of man, Mary, star of the sea.

The three girl friends were seated on the rocks, enjoying the evening scene and the air which was fresh but not too chilly. Many a time and oft were they wont to come there to that favourite nook to have a cosy chat beside the sparkling waves and discuss matters feminine, Cissy Caffrey and Edy Boardman with the baby in the pushcar and Tommy and Jacky Caffrey, two little curlyheaded boys, dressed in sailor suits with caps to match and the name H. M. S. Belleisle printed on both. For Tommy and Jacky Caffrey were twins, scarce four years old and very noisy and spoiled twins sometimes but for all that darling little fellows with bright merry faces and endearing ways about them. They were dabbling in the sand with their spades and buckets, building castles as children do, or playing with their big coloured ball, happy as the day was long. And Edy Boardman was rocking the chubby baby to and fro in the pushcar while that young gentleman fairly chuckled with delight. He was but eleven months and nine days old and, though still a tiny toddler, was just beginning to lisp his first babyish words. Cissy Caffrey bent over to him to tease his fat little plucks and the dainty dimple in his chin.

—Now, baby, Cissy Caffrey said. Say out big, big. I want a drink of water.

And baby prattled after her:

—A jink a jink a jawbo.

Guide

The “Nausicaa” episode takes place at twilight, around 8:00 pm, on the Sandymount strand, where Mr. Bloom is having a rest from a rather busy and draining day. After escaping the Citizen by carriage at the end of the "Cyclops" episode, Bloom and Martin Cunningham visited Mrs. Dignam to review her late husband’s insurance policy. In The Odyssey, a shipwrecked, storm-tossed, and exhausted Odysseus washes ashore in Phaeacia, where Princess Nausicaa finds him naked and brackish. ........

As Ulysses ventures into ever stranger and more disparate literary territories, its styles and voices will continue to shift, shaping our experience of the plot. ...... there is some debate over the narrative voice and perspective here. You might consider that the episode begins in the style of a cheap romance novel and/or women’s magazine

The “Nausicaa” episode opens on the beach at around 8:00 pm with three young women (Edy Boardman, Cissy Caffrey, and Gerty MacDowell), two toddler boys (Tommy and Jacky Caffrey), and a baby in a stroller. Within this group, Gerty quickly becomes the narrative’s central figure; the text focuses on her physique, her feelings, and her desires. Her characterization is heavily adorned with references to beauty products, fashion, and efforts at physical self-improvement (almost like an amalgamation of ads from a beauty magazine). In a nearby church and simultaneous to the events on the strand, a service for the Virgin Mary takes place; in these ways, the “Nausicaa” episode presents many of the patriarchy’s ideals of femininity: a beautiful object, a pure virgin, and refuge “to the stormtossed heart of man”.

Ch14 Oxen of the Sun

In a maternity hospital; language styles evolve from ancient to modern, symbolizing birth and life cycles.Deshil Holles Eamus. Deshil Holles Eamus. Deshil Holles Eamus.

Send us bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit. Send us bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit. Send us bright one, light one, Horhorn, quickening and wombfruit.

Hoopsa boyaboy hoopsa! Hoopsa boyaboy hoopsa! Hoopsa boyaboy hoopsa!

Universally that person’s acumen is esteemed very little perceptive concerning whatsoever matters are being held as most profitably by mortals with sapience endowed to be studied who is ignorant of that which the most in doctrine erudite and certainly by reason of that in them high mind’s ornament deserving of veneration constantly maintain when by general consent they affirm that other circumstances being equal by no exterior splendour is the prosperity of a nation more efficaciously asserted than by the measure of how far forward may have progressed the tribute of its solicitude for that proliferent continuance which of evils the original if it be absent when fortunately present constitutes the certain sign of omnipollent nature’s incorrupted benefaction. For who is there who anything of some significance has apprehended but is conscious that that exterior splendour may be the surface of a downwardtending lutulent reality or on the contrary anyone so is there unilluminated as not to perceive that as no nature’s boon can contend against the bounty of increase so it behoves every most just citizen to become the exhortator and admonisher of his semblables and to tremble lest what had in the past been by the nation excellently commenced might be in the future not with similar excellence accomplished if an inverecund habit shall have gradually traduced the honourable by ancestors transmitted customs to that thither of profundity that that one was audacious excessively who would have the hardihood to rise affirming that no more odious offence can for anyone be than to oblivious neglect to consign that evangel simultaneously command and promise which on all mortals with prophecy of abundance or with diminution’s menace that exalted of reiteratedly procreating function ever irrevocably enjoined?

Guide

The “Oxen of the Sun” episode takes place between 10:00 and 11:00 pm at the Holles Street Maternity Hospital, where Stephen is continuing his bender with three medical students (Dixon, Lynch, and Madden) and a few other miscellaneous Dubliners (Lenehan, Punch Costello, and Crotthers). Mr. Bloom will soon join this group, having taken a tram from Sandymount to Merrion Square in order to check on Mrs. Purefoy, who has been in labor at the hospital for three days.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew land on the island of Thrinacia, home of the sungod’s immortal sheep and longhorn cattle. Both Circe and Tiresias have warned Odysseus to avoid this island entirely; at the very least, they mustn’t harm Helios’s sacred oxen – sacred symbols of fertility – lest the gods punish the offenders with annihilation. ..................

Joyce uses a series of 32 parodies to represent the “embryonic development” he identified in the schema as his technique for the “Oxen of the Sun” episode. These parodies chart the growth of literary style from preliterate pagan incantations into Middle English, followed by the Latinate styles of Milton, imitations of satirists such as Swift, and eventually 19th century novelists such as Dickens. This episode, then, is the ultimate authorial powerflex: Joyce exerts his mastery of every form of writing that led to the birth of Ulysses. Demonstrating Joyce’s unparalleled literary dexterity and depth of knowledge, this episode is an impressive execution of an audacious idea; Joyce estimated that he spent 1,000 hours writing it. Yet none of that makes it particularly fun to read.

Because these parodies of various styles dominate the surface of the narrative, “Oxen” is perhaps the most challenging episode to get through. Some might even call it tedious. Joyce himself described it as “the most difficult episode […] both to interpret and to execute” (Letters I 137). Harriet Shaw Weaver, Joyce’s benefactor, wrote with some bite that “Oxen” “might also have been called ‘Hades,’ for the reading of it is like being taken the rounds of hell” (JJ 476). So yeah, it’s hard. But having come this far in your reading of Ulysses, you’ll go a little further, even if that means spending a few hours in hell. When you re-read the novel in a few years, you might skim or even skip it. For now, though, let’s do our best to get through it together, because there are certainly some clever moments to enjoy and many important details to gather. At the very least, we can appreciate the episode’s ingenuity.

Ch15 Circe

In a brothel (Nighttown), Bloom and Stephen experience hallucinations — chaos and transformation.(The Mabbot street entrance of nighttown, before which stretches an uncobbled tramsiding set with skeleton tracks, red and green will-o’-the-wisps and danger signals. Rows of grimy houses with gaping doors. Rare lamps with faint rainbow fans. Round Rabaiotti’s halted ice gondola stunted men and women squabble. They grab wafers between which are wedged lumps of coral and copper snow. Sucking, they scatter slowly. Children. The swancomb of the gondola, highreared, forges on through the murk, white and blue under a lighthouse. Whistles call and answer.)

THE CALLS: Wait, my love, and I’ll be with you.

THE ANSWERS: Round behind the stable.

(A deafmute idiot with goggle eyes, his shapeless mouth dribbling, jerks past, shaken in Saint Vitus’ dance. A chain of children ’s hands imprisons him.)

THE CHILDREN: Kithogue! Salute!

THE IDIOT: (Lifts a palsied left arm and gurgles.) Grhahute!

THE CHILDREN: Where’s the great light?

THE IDIOT: (Gobbling.) Ghaghahest.

(They release him. He jerks on. A pigmy woman swings on a rope slung between two railings, counting. A form sprawled against a dustbin and muffled by its arm and hat snores, groans, grinding growling teeth, and snores again. On a step a gnome totting among a rubbishtip crouches to shoulder a sack of rags and bones. A crone standing by with a smoky oillamp rams her last bottle in the maw of his sack. He heaves his booty, tugs askew his peaked cap and hobbles off mutely. The crone makes back for her lair, swaying her lamp. A bandy child, asquat on the doorstep with a paper shuttlecock, crawls sidling after her in spurts, clutches her skirt, scrambles up. A drunken navvy grips with both hands the railings of an area, lurching heavily. At a corner two night watch in shouldercapes, their hands upon their staffholsters, loom tall. A plate crashes: a woman screams: a child wails. Oaths of a man roar, mutter, cease. Figures wander, lurk, peer from warrens. In a room lit by a candle stuck in a bottleneck a slut combs out the tatts from the hair of a scrofulous child. Cissy Caffrey’s voice, still young, sings shrill from a lane.)

CISSY CAFFREY:

I gave it to Molly

Because she was jolly,

The leg of the duck,

The leg of the duck.

(Private Carr and Private Compton, swaggersticks tight in their oxters, as they march unsteadily rightaboutface and burst together from their mouths a volleyed fart. Laughter of men from the lane. A hoarse virago retorts.)

THE VIRAGO: Signs on you, hairy arse. More power the Cavan girl.

CISSY CAFFREY: More luck to me. Cavan, Cootehill and Belturbet. (She sings.)

I gave it to Nelly

To stick in her belly,

The leg of the duck,

The leg of the duck.

(Private Carr and Private Compton turn and counterretort, their tunics bloodbright in a lampglow, black sockets of caps on their blond cropped polls. Stephen Dedalus and Lynch pass through the crowd close to the redcoats.)

PRIVATE COMPTON: (Jerks his finger.) Way for the parson.

PRIVATE CARR: (Turns and calls.) What ho, parson!

CISSY CAFFREY: (Her voice soaring higher.)

She has it, she got it,

Wherever she put it,

The leg of the duck.

(Stephen, flourishing the ashplant in his left hand, chants with joy the introit for paschal time. Lynch, his jockeycap low on his brow, attends him, a sneer of discontent wrinkling his face.)

STEPHEN: Vidi aquam egredientem de templo a latere dextro. Alleluia.

(The famished snaggletusks of an elderly bawd protrude from a doorway.)

THE BAWD: (Her voice whispering huskily.) Sst! Come here till I tell you. Maidenhead inside. Sst!

STEPHEN: (Altius aliquantulum.) Et omnes ad quos pervenit aqua ista.

THE BAWD: (Spits in their trail her jet of venom.) Trinity medicals. Fallopian tube. All prick and no pence.

Guide

Ok, this one’s a doozy. Beginning shortly before midnight, the “Circe” episode uses the form of a play to portray a kaleidoscopic blend of real and imaginary happenings over the course of an hour in Dublin’s brothel district. “Circe” takes up nearly 150 pages in the Gabler edition of Ulysses, making it about as long as the first eight episodes of the novel combined.

Worried over Stephen’s drunken condition, Bloom has followed him into Nighttown in hopes of taking care of him. Between the end of “Oxen” and the start of “Circe,” a sundering occurred between Stephen and Buck Mulligan in Westland Row Station; perhaps Buck simply abandoned Stephen, or maybe there was a physical confrontation. Regardless, Buck and Haines have departed without Stephen on the last train toward the Tower in Sandycove. As Stephen anticipated all the way back in “Telemachus,” he will not sleep there tonight. Buck has usurped his place. Accompanied by Lynch (and trailed by Bloom), Stephen has taken the train from Westland Row to Amiens Station and is now on his way to a brothel. Bloom is hustling to catch up after stopping briefly to buy snacks.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew land on Aeaea, and a team of scouts discover the palace of Circe, a witch goddess. Circe invites Odysseus’s men inside for a drink and then magically turns them into pigs. One man escapes to tell Odysseus about their comrades’ fate and Circe’s trickery. Odysseus bravely hopes to rescue his men from Circe’s enchantment; on the way to her house, Odysseus receives help from Hermes, who offers him a plan and equips him with moly, a magical herb that will protect him from Circe’s witchcraft. The plan works: the moly counters Circe’s magic, she swoons for Odysseus and transforms his crew from pigs back into men. Odysseus and Circe then make love. For a year. Finally, some of Odysseus’s crew shake him from the madness of his long Circean interlude and compel him to resume the journey home to Ithaca.

In early spring 1920, Joyce emerged from the 1,000 hours he had spent writing “Oxen” and turned his attention to “Circe.” He expected that this episode, like the few he had recently composed, would take him two to three months to complete. Little did he know that “Circe” would require eight drafts and take over half a year to write (Letters), much less that it would have the power to bewitch his creative process and entirely transform Ulysses. This episode, with its exhaustive reprises of virtually every character, object, and idea introduced in the novel thus far, would compel Joyce to revise much of what he had previously written. Joyce estimated that he wrote a third of Ulysses at the proof stage of the revision process (Beach 58), arranging codependent details all over the novel and weaving a web of intratextual puzzles that will “keep the professors busy for centuries” (JJ 521).

Ch16 Eumaeus

Bloom and Stephen meet in a cabman’s shelter — uncertain recognition, father-son connection hinted.Preparatory to anything else Mr Bloom brushed off the greater bulk of the shavings and handed Stephen the hat and ashplant and bucked him up generally in orthodox Samaritan fashion which he very badly needed. His (Stephen’s) mind was not exactly what you would call wandering but a bit unsteady and on his expressed desire for some beverage to drink Mr Bloom in view of the hour it was and there being no pump of Vartry water available for their ablutions let alone drinking purposes hit upon an expedient by suggesting, off the reel, the propriety of the cabman’s shelter, as it was called, hardly a stonesthrow away near Butt bridge where they might hit upon some drinkables in the shape of a milk and soda or a mineral. But how to get there was the rub. For the nonce he was rather nonplussed but inasmuch as the duty plainly devolved upon him to take some measures on the subject he pondered suitable ways and means during which Stephen repeatedly yawned. So far as he could see he was rather pale in the face so that it occurred to him as highly advisable to get a conveyance of some description which would answer in their then condition, both of them being e.d.ed, particularly Stephen, always assuming that there was such a thing to be found. Accordingly after a few such preliminaries as brushing, in spite of his having forgotten to take up his rather soapsuddy handkerchief after it had done yeoman service in the shaving line, they both walked together along Beaver street or, more properly, lane as far as the farrier’s and the distinctly fetid atmosphere of the livery stables at the corner of Montgomery street where they made tracks to the left from thence debouching into Amiens street round by the corner of Dan Bergin’s. But as he confidently anticipated there was not a sign of a Jehu plying for hire anywhere to be seen except a fourwheeler, probably engaged by some fellows inside on the spree, outside the North Star hotel and there was no symptom of its budging a quarter of an inch when Mr Bloom, who was anything but a professional whistler, endeavoured to hail it by emitting a kind of a whistle, holding his arms arched over his head, twice.

Guide

Picking up the action immediately after the end of “Circe,” the “Eumaeus” episode covers the time between roughly 12:45 and 1:40 am. Mr. Bloom welcomes Stephen out of his stupor and takes him to a nearby cabman’s shelter for a quiet moment and some sustenance.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus returns home to Ithaca, emerges from an Athena-induced haze, disguises himself as a beggar, goes to the hut of Eumaeus, his swineherd. Rather than reveal himself immediately, Odysseus tells Eumaeus false stories about his identity and origin. After Eumaeus passes a loyalty test, Odysseus reveals his true identity. Later in Eumaeus’s hut, Odysseus is united with his son, Telemachus. Together, the three men plot an attack on the suitors plaguing Odysseus’s home and besetting his wife Penelope.

The style of the “Eumaeus” episode, identified by Joyce in his schemas as “narrative (old),” has been met with divergent critical opinions. Richard Ellmann claims that the episode “struggles clumsily for the right expression” (Ellmann 151), while Stanley Sultan describes it as “the attempt of a poorly-educated man to impress by discoursing with sophisticated eloquence” (Sultan 364). David Hayman calls the episode “a tired, threadbare, flatulent narrative larded with commonplaces” whereby “the arranger conveys with surprising accuracy the drink and fatigue-dulled sentiments of both protagonists” (Hayman 102-03). Maybe.

In my opinion, the most useful understanding of the style of this episode relies on the Uncle Charles Principle. In short, “the Uncle Charles Principle entails writing about someone much as that someone would choose to be written about” (Kenner 21). Applying this concept to the current episode, “Eumaeus” is written in the style that Bloom would have employed if he himself had written the episode; indeed, Bloom later announces his intention to compose exactly this piece of literature: “suppose he were to pen something out of the common groove (as he fully intended doing) at the rate of one guinea per column. My experiences, let us say, in a Cabman’s Shelter” (16.1229-31). So, rather than condemning “Eumaeus” as stilted, over-ornamented prose with garbled syntax and imprecise diction, we might instead consider the episode’s use of Bloom’s own literary style (flawed as it may be) as the ultimate celebration of Bloom himself (flawed as he may be). By ceding such control to Mr. Bloom, Joyce offers “the book’s most profound tribute to its hero” (Kenner 38). With this gesture in mind, the episode’s flabby sentences and cringe-worthy cliches become endearing a la Bloom himself. The episode’s inferior style, though, is also a demonstration of Joyce’s extreme facility with language. Just as it takes a very good piano player to play a song really poorly (you have to know the exact wrong notes to play to make it sound truly awful), it takes an immensely talented writer to intentionally write this badly. Bearing this in mind, the reader can appreciate the humour embedded in the style of this particular episode.

Ch17 Ithaca

Bloom takes Stephen home; order is restored but questions remain.What parallel courses did Bloom and Stephen follow returning?

Starting united both at normal walking pace from Beresford place they followed in the order named Lower and Middle Gardiner streets and Mountjoy square, west: then, at reduced pace, each bearing left, Gardiner’s place by an inadvertence as far as the farther corner of Temple street: then, at reduced pace with interruptions of halt, bearing right, Temple street, north, as far as Hardwicke place. Approaching, disparate, at relaxed walking pace they crossed both the circus before George’s church diametrically, the chord in any circle being less than the arc which it subtends.

Of what did the duumvirate deliberate during their itinerary?

Music, literature, Ireland, Dublin, Paris, friendship, woman, prostitution, diet, the influence of gaslight or the light of arc and glowlamps on the growth of adjoining paraheliotropic trees, exposed corporation emergency dustbuckets, the Roman catholic church, ecclesiastical celibacy, the Irish nation, jesuit education, careers, the study of medicine, the past day, the maleficent influence of the presabbath, Stephen’s collapse.

Did Bloom discover common factors of similarity between their respective like and unlike reactions to experience?

Both were sensitive to artistic impressions, musical in preference to plastic or pictorial. Both preferred a continental to an insular manner of life, a cisatlantic to a transatlantic place of residence. Both indurated by early domestic training and an inherited tenacity of heterodox resistance professed their disbelief in many orthodox religious, national, social and ethical doctrines. Both admitted the alternately stimulating and obtunding influence of heterosexual magnetism.

Were their views on some points divergent?

Stephen dissented openly from Bloom’s views on the importance of dietary and civic selfhelp while Bloom dissented tacitly from Stephen’s views on the eternal affirmation of the spirit of man in literature. Bloom assented covertly to Stephen’s rectification of the anachronism involved in assigning the date of the conversion of the Irish nation to christianity from druidism by Patrick son of Calpornus, son of Potitus, son of Odyssus, sent by pope Celestine I in the year 432 in the reign of Leary to the year 260 or thereabouts in the reign of Cormac MacArt († 266 A.D.), suffocated by imperfect deglutition of aliment at Sletty and interred at Rossnaree. The collapse which Bloom ascribed to gastric inanition and certain chemical compounds of varying degrees of adulteration and alcoholic strength, accelerated by mental exertion and the velocity of rapid circular motion in a relaxing atmosphere, Stephen attributed to the reapparition of a matutinal cloud (perceived by both from two different points of observation Sandycove and Dublin) at first no bigger than a woman’s hand.

Was there one point on which their views were equal and negative?

The influence of gaslight or electric light on the growth of adjoining paraheliotropic trees.

Guide

The “Ithaca” episode continues the action of the novel more or less seamlessly from the end of “Eumaeus” (which itself is continuous from the end of “Circe”). The time at the start of the present episode is perhaps 1:40 am. Mr. Bloom and Stephen Dedalus are walking north from the cabman’s shelter to the Bloom’s home in Eccles Street, a .8 mile walk that should take them roughly 20 minutes.

In The Odyssey, Odysseus has finally returned to his home on the rocky island of Ithaca. After revealing himself to his son in Eumaeus’s hut, the heroes plan Odysseus’s recapturing of his palace and assault on the suitors; he will remain disguised as a beggar until he strings his mighty bow and shoots an arrow through a dozen axes, proving his strength and precision.

The notion of precision might be useful as we orient ourselves to the style of the “Ithaca” episode. In the Gilbert schema, Joyce listed the technique for this episode as “catechism (impersonal),” a multivalent reference. Most obviously, the term catechism applies to the Catholic texts that use a series of questions and answers to define the theological and moral beliefs of the church. Joyce would have been intimately familiar with this form of writing from his Jesuit education. Just as influential, though, a catechetical or Socratic method of question and answer would have been central to the classroom instruction Joyce experienced in his late 19th century schooling; ..............and this meticulous form replicates Odysseus’s precision with the bow and arrow.

But the episode also playfully pushes this precision to an absurd extreme, an over-the-top exactitude Hugh Kenner credits to Bloom’s favorite weekly magazine, Tit-Bits: “each issue […] contained a page called ‘Tit-Bits Inquiry Column’: answers to questions no one would have thought to ask” (Kenner 145). ....................

Like all of Ulysses, then, “Ithaca” elevates Bloom into the sphere of timeless epic heroes while also exposing him to be profoundly unexceptional. .................

It may be no surprise, then, that “Ithaca,” which Joyce called the “ugly duckling of the book,” was his “favourite episode” in the novel

Ch18 Penelope

Molly Bloom’s monologue mirrors Penelope's loyalty and humanity — a stream of consciousness "yes."Yes because he never did a thing like that before as ask to get his breakfast in bed with a couple of eggs since the City Arms hotel when he used to be pretending to be laid up with a sick voice doing his highness to make himself interesting for that old faggot Mrs Riordan that he thought he had a great leg of and she never left us a farthing all for masses for herself and her soul greatest miser ever was actually afraid to lay out 4d for her methylated spirit telling me all her ailments she had too much old chat in her about politics and earthquakes and the end of the world let us have a bit of fun first God help the world if all the women were her sort down on bathingsuits and lownecks of course nobody wanted her to wear them I suppose she was pious because no man would look at her twice I hope Ill never be like her a wonder she didnt want us to cover our faces but she was a welleducated woman certainly and her gabby talk about Mr Riordan here and Mr Riordan there I suppose he was glad to get shut of her and her dog smelling my fur and always edging to get up under my petticoats especially then still I like that in him polite to old women like that and waiters and beggars too hes not proud out of nothing but not always if ever he got anything really serious the matter with him its much better for them to go into a hospital where everything is clean but I suppose Id have to dring it into him for a month yes and then wed have a hospital nurse next thing on the carpet have him staying there till they throw him out or a nun maybe like the smutty photo he has shes as much a nun as Im not yes because theyre so weak and puling when theyre sick they want a woman to get well if his nose bleeds youd think it was O tragic and that dyinglooking one off the south circular when he sprained his foot at the choir party at the sugarloaf Mountain the day I wore that dress Miss Stack bringing him flowers the worst old ones she could find at the bottom of the basket anything at all to get into a mans bedroom with her old maids voice trying to imagine he was dying on account of her to never see thy face again though he looked more like a man with his beard a bit grown in the bed father was the same ......

Guide

Since the beginning of our odyssey through Bloomsday, we have been journeying toward Molly’s perspective, delivered here in “Penelope” unfiltered and with minimal interruption. The promise of hearing from Molly in the final episode has been a motivating interest, pulling us through the novel; she seems certain to provide the last piece of the puzzle. Joyce referred to Molly’s monologue in “Penelope” as “the indispensable countersign to Bloom’s passport to eternity” (Letters I 160). Sure enough, we can spend eternity reading this novel and this episode in particular, experiencing the text differently each time. In typical Joycean fashion, “Penelope” will confound our desires for closure and satisfaction, but it guarantees a life’s worth of interesting moments to scrutinize.

Some readers of “Penelope” will find Molly offensive. D. H. Lawrence described the episode as “the dirtiest, most indecent, obscene thing ever written” (qtd. in Chabon). Its obscenity contributed to Ulysses being banned in the English-speaking world for over a decade after its initial publication in 1922. A friend of Joyce’s named Mary Colum denounced “Penelope,” calling it “an exhibition of the mind of a female gorilla” (qtd. in Herring 57). While that description seems a bit harsh on Molly, the audacity of a man attempting to represent Woman (much less any individual woman) was roundly rejected in early feminist reactions to the text. Many felt that Joyce had misunderstood and misrepresented the female mind and perspective. Indeed, Molly Bloom herself visited Joyce in dreams, castigating him for “meddling” in her business (Lawrence 72).

Or, maybe Joyce was a protofeminist, creating Molly as a sexually liberated woman with freely expressed desires and the agency to speak and do as she wishes. In later criticism, scholars began to recognize a shared purpose between feminism and Joyce’s efforts in Ulysses generally and “Penelope” specifically to expose and disrupt the patriarchal conventions of literature and representation (Lawrence 74), and some even considered Molly’s soliloquy the paragon of écriture féminine, a style whereby language “is fluidly organized and freely associative. Thus, it has the capacity to both reflect and create human experience beyond the control of patriarchy” (Tyson 93). In this view, “Penelope” opens the door to new post-patriarchal literary forms.

Outside of feminism, scholars have shifted their reading of Molly in each generation. In the 1920s, she was obscene. In the 30s, scholars sought to canonize Joyce and Ulysses, so they therefore avoided criticizing her vulgarity “for fear that in impugning Molly’s reputation, they would tarnish Joyce’s” (McCormick 29); instead, they described her as an idealized force of Nature, a Gaia earth-mother-goddess, suppressing her sexuality. Once Joyce had been safely canonized, it became possible for critics in the 50s and 60s to attack Molly’s sensuality and label her a “whore,” reflecting a larger post-WWII antifeminist reaction (McCormick 29). Then, in the 70s and 80s, post-structuralists couch her “language, desire, and even her very subjectivity” as products of “her historical formation” (McCormick 33). To be sure, you can spend years delving deeply into the scholarly lenses and debates that have sought to define Molly Bloom. I myself got a bit lost in this rabbit hole while preparing to write this episode guide, and I could have happily spent much longer weighing brilliant people’s opinions about this fascinating character.

However, the project at hand, as always on this site, is to support you as you complete your reading of Ulysses. I will reference various scholars’ ideas where relevant in this guide, but I intend to keep focused primarily on the text itself.

So, let’s review what we, as readers of Ulysses, know about this woman. A 33 year old soprano of local fame, Molly Bloom has been married for 15 years to Leopold Bloom, with whom she has had two children: a daughter, Milly, who just turned 15 yesterday, and a son, Rudy, who died in infancy a decade ago. Molly Tweedy was born and raised in Gibraltar because her father, Major Brian Tweedy, was stationed there as a soldier in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers unit of the British military. On this day, June 16th, 1904, she has had extramarital sex with Blazes Boylan, the man who is managing her upcoming concert tour of Belfast and Liverpool. Also on this day, she received breakfast in bed from her husband and tossed a coin to a beggar.

In The Odyssey, Penelope has waited faithfully for 20 years for her husband’s return from the Trojan War, spending the last four years or so rebuffing over 100 suitors seeking her hand in remarriage. Under this pressure, she devises an ingenious plan to delay selecting a new husband: she claims, citing tradition and decency, that she must weave a funeral shroud for her father-in-law prior to remarrying. She works at her loom all day, and then each night secretly unweaves her work from the previous day. Just as Penelope, in her cleverness, is a perfect match for Odysseus, we might say the same of Molly and Leopold Bloom in their shared characteristics of wantonness, sensitivity, and charity.

The “Penelope” episode consists of eight “sentences” separated by paragraph breaks. There is no punctuation in the final version of the text, although “much of the punctuation was deleted only in the proofs, after most of her well-formed sentences had been constructed” (M. Ellmann 102). In many ways, Molly’s flowing stream of consciousness is unique in all of literature. Joyce wrote that “Penelope has no beginning, middle or end” (Letters I 172), and he listed in the schema ∞ as the hour for this episode. This symbol has a variety of possible meanings: it represents infinity and is an 8 lying down on its side, indicating the 8 sentences that comprise the episode while also depicting the image of Molly lying down in bed.

References

Online Guide By Patrick Hastings

Podcasts

BBC - In Our Time Also contains links

BBC Radio 4 Archive - 4 links

On The Road With Penguin Classics with Henry Eliot (Spotify link but others are available)

Articles

Woolf’s Reading of James Joyce’s Ulysses, 1918-1920 (link at the bottom for 1922 -1941)

Videos

James Joyce Ulysses Dublin Tour

The World of James Joyce: His Life & Work documentary (1986)